Don’t tell. But this year for Christmas, my dad is giving my mom the best Christmas present ever. He’s invested money in this gift because he’s giving one not only to my mom, but also to his children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren—all 79 of us.

But his greatest investment has been time.

I’ve had a front seat to the writing of Erma’s Story. And what I’ve seen is a labor of love—a gift from my 92-year-old father to my 97-year-old mother, who has long looked for someone to write her story. My dad saw this yearning, so he laid aside what he loves to write—church history—and set to work.

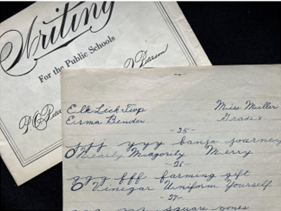

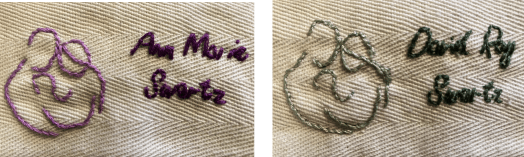

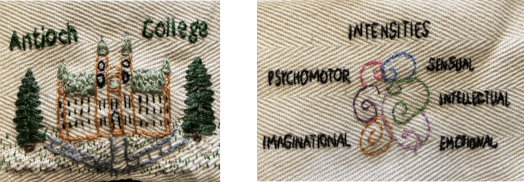

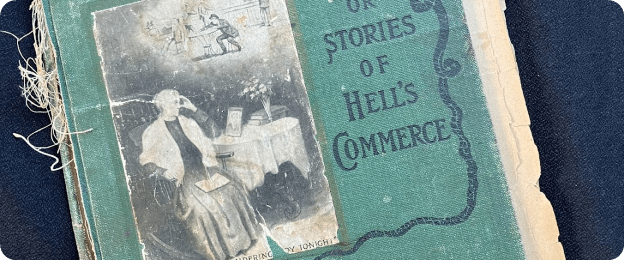

On a spare bed, he laid out the scraps of my mom’s life—diaries, journals, school papers, childhood gifts, photos, scrapbooks, an egg grader, a Hillside Farm butter wrapper, an old feedbag, ledgers, a box of rocks, sermon notebooks, ration books, tattered children’s books, school papers and report cards. Meticulously, he searched through diaries for anecdotes and on newspapers.com for historical facts. He searched through recorded and transcribed tapes for conversations. He created timelines and curated what he found into a coherent and gripping account.

And all this with love.

The same love he’s been showing my mom throughout their daily, elderly lives. I’ve also had a front seat for this, going to their house nearly every day, sometimes multiple times, sometimes overnight. He tucks her in at night—pulling the covers over her shoulders, pushing the play button on her audio Bible, and dimming the lights. He counts her medicine into pill boxes and meets forgetfulness with kindness and generosity.

This is old love, an intimacy built on deliberate decisions to understand, appreciate, and celebrate each other.

As my dad and I sat together for this project, his tenderness for my mother kept bleeding through. When her childhood home burned down and she yearned over a struggling sister and a classmate stole her treasured pencil box, his voice would catch and his eyes glisten. When she and her siblings told stories, he’d throw back his head and laugh. “Such good story tellers,” he’d say. “They know just how to put it all together.” This from a man who is correct, precise, and concise with his diction, admiring the Benders, who bend grammar and syntax to flavor their stories.

Our family will gather as usual this Christmas. We’ll each receive our books, likely autographed with both of their names. And I’m guessing we’ll all learn to sing “Because It’s Christmas Time,” a song found in this book—new to us, but part of our mom’s childhood Christmases.

After the holidays, Dad will go back to writing church history. But only for a season. Health and energy holding, he hopes to get back to Erma’s story. Coming up will be the next season of Mom’s life, including the beginnings of my parent’s romance.

And once again, I look forward to taking a front seat as two distinct plotlines unfold—the budding of young love in the pages of a book and, in the here and gritty now, love that is old.

And flowering.