We’ve found the right place. We know as soon as we step inside. The Schuster Performing Arts Center is full of grey heads and lines for elevators. Some of us eschew the elevators and climb the elliptical staircase to the balconies. But though we think ourselves fit, we stop at each landing—to admire the Wintergarden in the lobby below. And to catch a breath.

The 2,300-seat theatre begins to fill. The couple beside us discusses orthopedic shoes. Just over from us, a woman moves to a row below.

“Down here, I can see better through my bifocals,” she says to her husband, who follows behind grumbling.

Just a few seats away, a couple holds hands, wrinkled, blue-veined hands. A young guy walks in. He’s escorting a woman with a cane, probably his grandma. Nice guy to come with his grandma. Wise grandma to show him bygone days.

Finally, the show begins: The Simon and Garfunkel Story.

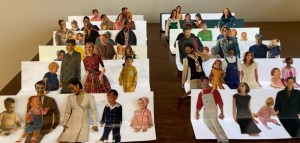

This touring show tells the story of the rise of Simon and Garfunkel by blending their songs with original film footage of the times.

We were young once, the show reminds us. And cool. We see the evidence on the screen—beads, long hair, tie-dye shirts, daisies, hippie buses, bell bottoms, and peace signs. The musicians sing about how groovy we were back then, how inclined to drop out of the rat race:

Slow down, you move too fast

You got to make the morning last

Just kicking down the cobblestones

Looking for fun and feelin’ groovy

Ba da da da da da,da, da, feelin’ groovy.

But if we were chill, we also lived through turbulent times. That proof’s in the images, too: war, draft-card burning, tear gas, generational conflict, and protests over racial injustice. The musicians sing about this:

And the sign flashed out its warning

In the words that it was forming

And the sign said, “The words of the prophets are written on the subway walls

And tenement halls

And whispered in the sound of silence.

Way back in 1968, when they released “Old Friends,” Simon and Garfunkel must have foreseen the future gatherings of grey-heads who lived through this turmoil.

Can you imagine us years from today

Sharing a park bench quietly?

How terribly strange to be 70

Old friends, memory brushes the same years

Silently sharing the same fears.

There’s a pause before the pickup notes of the performance’s climax—“Like a Bridge Over Troubled Water.” This song brings a promise to the weary, to the crying, to those in dark times.

Like a bridge over troubled water, the musicians sing, I will lay me down . . . I will comfort you. . . I’ll ease your mind.

Back when this song was new, we were young and mostly absorbed in our own pain. But we sang those lyrics like we meant them. And maybe we did. Because now many of us care for two generations or three or maybe even four. Over and over, we lay ourselves down. This is the calling and privilege of being 70.

We’re a bit sobered, thinking of those we love. But the evening isn’t over. We come alive with “The Boxer,” a song about someone who doesn’t give up the fight. The lyrics and music are punchy. And during the filler syllables between the stanzas, those of us who, back in the day, waved flashlights at rock concerts, now pull out cell phones and move them with the music.

Simon and Garfunkel are right. It’s terribly strange to be 70. And fun. Even somewhat groovy.